Caspar David Friedrich was born in September 1774 in Greifswald, a university town located in Pomerania, in the north of modern-day Germany, facing the Baltic Sea through its port. He was the sixth of ten siblings, born to a soap and candle manufacturer. His life and work were marked by the death of his mother when he was seven years old, and later the death of his brother.

Caspar David Friedrich was born in September 1774 in Greifswald, a university town located in Pomerania, in the north of modern-day Germany, facing the Baltic Sea through its port. He was the sixth of ten siblings, born to a soap and candle manufacturer. His life and work were marked by the death of his mother when he was seven years old, and later the death of his brother.

The latter was particularly tragic for the artist, as his brother drowned after saving Caspar from falling into a frozen lake. It is not surprising that the melancholic language of his paintings or certain themes, such as those in one of his most famous works, “The Sea of Ice” or “The Polar Sea” (“Das Eismeer”), reflect this experience.

His father’s strict, Protestant principles and teachings from theologian Gotthard Ludwig Kosegarten had a profound influence on the future painter, shaping his worldview and his special relationship with nature: “…I have to immerse myself in what surrounds me, join the clouds and the rocks, to be what I am. I need solitude to converse with nature.”

At the age of twenty, he decided to enroll in the Academy of Copenhagen, which was considered one of the most liberal institutions in Europe. Under the tutelage of great landscape masters such as Abildgaard, Friedrich learned to copy plaster models and portray the human body. In 1894, he moved to the Academy of Dresden, attracted by a city that in the 18th century was known as the “German Florence” due to its beauty and rich art collections. Friedrich regularly participated in art exhibitions that were held frequently in the city, and his paintings were already well-received there.

This intense period of study in Dresden concluded in the spring of 1801. It was from this moment that the artist began to focus on what would become his own lyrical style of painting. Around 1808, Friedrich completed his first masterpieces, such as “The Cross on the Mountain (The Tetschen Altar),” which received wide public acclaim. However, this success did not seem to satisfy the painter, as some of his contemporaries testified that he had already attempted to take his own life once. According to the painter, “Death is the romantic beginning of our life. Death is… life.”

One of his masterpieces and one of the boldest canvases of German Romanticism is “Monk by the Sea”, painted around 1808. Friedrich breaks with all traditions; there is no depth due to perspective, as it is lost in an expanse of clouds and sea. This work is often interpreted as a meditation on the immensity of the Universe.

At this point, painting becomes an instrument for communicating with God. His landscapes are enveloped in fog; snow abounds, covering the already withered nature, and shadows with Gothic churches steeped in religiousness appear almost omnipresent, evoking feelings of Christian hope.

The recurrent presence of churches and Gothic ruins in his paintings and those of other artists of the 19th century is part of the phenomenon that spread throughout Europe during the Romantic period and is known as historicism.

This profusion of somber and strongly religious themes begins to impregnate the artist’s spirit, and he begins to withdraw into himself and turn to silence.

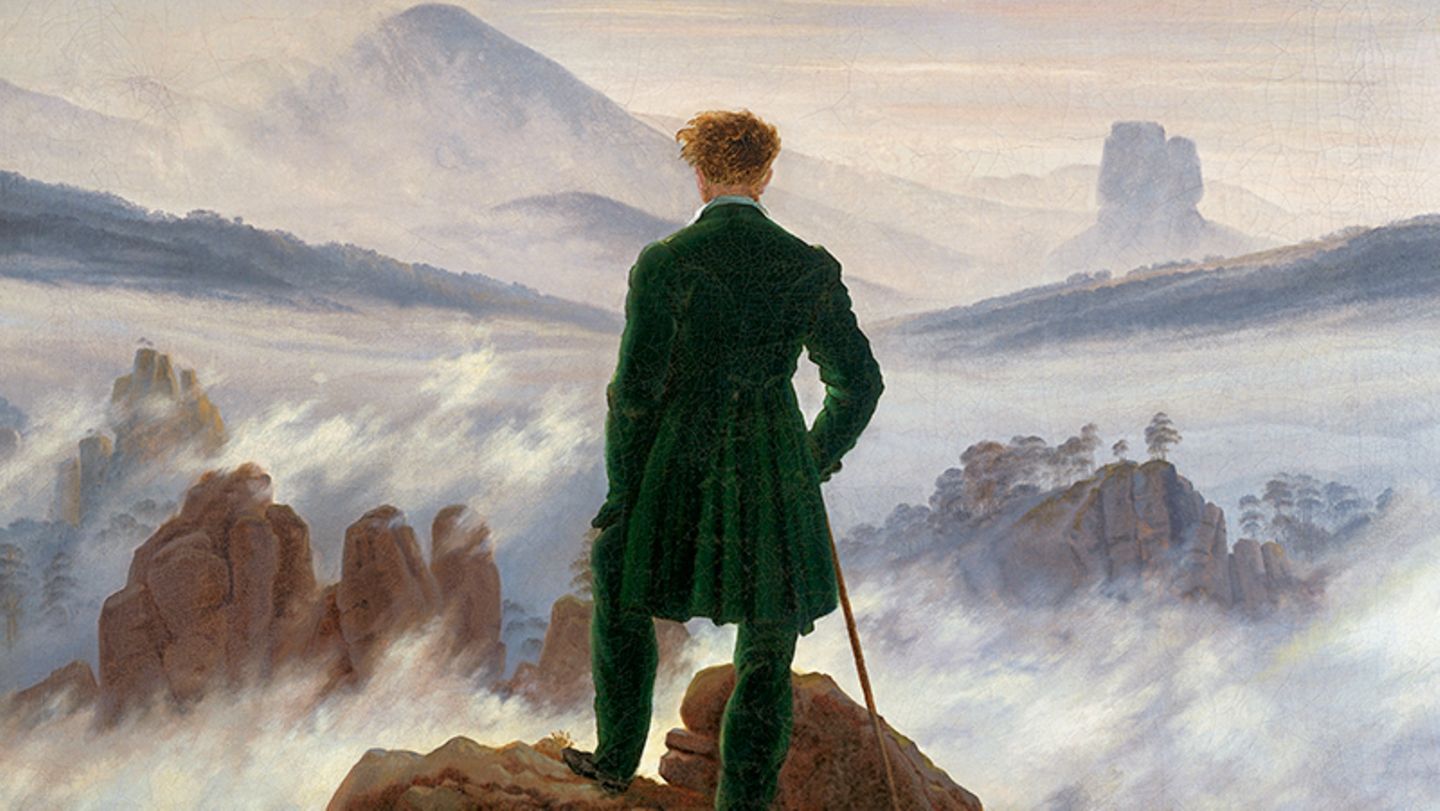

And that is one of Friedrich’s great virtues, to transport us to a world of silence. His human figures turn their backs to us; they are facing away from our presence… they are not with us. These figures do not speak to the viewer, nor do they even communicate with each other. They seem comforted in their lethargic solitude.

In an era when many Nordic artists are attracted to Italy, it is almost surprising that Friedrich never decided to travel there during his lifetime. On the contrary, he feels genuine contempt for the Italianizing fashion of his contemporaries. He is not interested in the luminosity of the South or in the painting of German artists residing in Italy. He is too tied to a Nordic conception of landscape to succumb to the fascination for Italy.

In 1818, Friedrich married Caroline Bommer, about whom little is known. The influence of this event is appreciated in his work, especially in the fact that from now on, female representations multiply in the artist’s canvases. He even introduces new friendly elements where there were only rocks and solitude before.

Towards 1830, Caspar seemed to retreat even further into his world of lyrical solitude of cliffs, clouds, and seas. The artist seemed to be fully aware that his art only had something to say to his closest friends who knew him best. The artist’s twilight was approaching. In 1835, Friedrich suffered a stroke that left him paralyzed in his arms and legs. It was the end of his artistic career. The end of a fruitful painting career, although his life continued for five more painful years. Finally, in May 1840, Caspar passed away, unable to even hold a pencil and with serious mental problems.

Soon after, he was almost completely forgotten. His painting was so tied to a subjective mood that while some admired it, others could hardly tolerate it. But it was the intrinsic nature of his art that made him stand out from all his successors.

Rediscovered, he is now considered the brilliant painter of calmness. But it is important to consider that his painting influenced beyond superficial romanticism. Friedrich did not paint for pure pleasure but tried to represent the silent truth of the hidden forces of nature and the unanswered sublimity of God. “A man who has discovered the tragedy of the landscape.”